Settlement Study: Tyonek, Alaska

By Catharina Laan

Spring Semester 2020

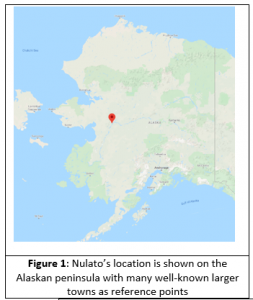

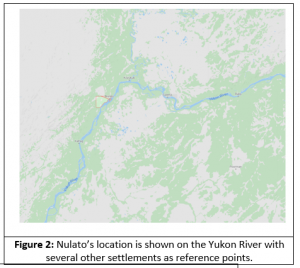

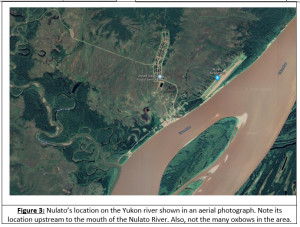

Tyonek is a coastal city, located in south central coastal city of Alaska. It is a small settlement of native Alaskans. Specifically, it is located on the northwest shore of Cook Inlet, 45 miles southwest of Anchorage. The people of Tyonek are part of Athabascan region and have the dialect called Dena’ina. It is the only community in the Kenai Peninsula Borough that is not located directly on the Kenai Peninsula. It lies at approximately at approximately 61 ° 04′ N Latitude, 151 ° 08′ W Longitude. The village, encompassing 22 square miles of land and 3 square miles of water.

Today there are about 190 residents in Tyonek; however, the Tyonek Native Corporation (TNC) has over 800 shareholders that can practice subsistence hunting, fishing, and gathering within the District. The community has one school that currently educates about 35 students in grades K-12. The Tyonek community is accessible by plane or boat, but is not connected by road to Anchorage.

In describing the physical geography of Tyonek, there are many aspects to address this. The physiography, climate, state whether it has any permafrost, ecoregion, and natural hazards will be described.

First thing to describe in this settlement its physiography which is located in the Pacific Mountains and Valleys Region.

Second, is to describe the climate of Tyonek which is located in the South Central region and within that there is variation due to the location of its latitude, maritime, continental land influences. Climate is generally mild for the region, with average winter temperatures ranging from 4 ° to 22 ° F and average summer temperatures ranging from 46 ° to 65 ° F. Temperature extremes have been recorded from -27 ° to 91 ° F. The average annual precipitation is 23 inches, including 82 inches of snow. It generally has moderate precipitation and mild winters.

Tyonek is generally free of permafrost.

The type of ecoregion that Tyonek is located in is on the first level is Temperate Continental, on the 2nd level it is Coast Mountains Boreal, and finally, on the third level of the ecoregion it is Cook Inlet Basin-Susitna Lowland.

The natural hazards in Tyonek are fires, flooding, earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes eruptions. In the 1930’s where the original village existed at that time, there was a big flood, so the village had to move to higher ground. So, they moved 7 miles northeast to a new site, on bluff, and the town is still called “Tyonek’.

In the case of earthquakes, in the last 60 years, there was a big earthquake and it occurred on March 27, 1964, magnitude of 9.2 with epicenter in the Prince William Sound region of Alaska. This 1964 Alaskan earthquake, also known as the Great Alaskan earthquake and Good Friday earthquake, its affects went across south central Alaska. This earthquake caused ground fissures, collapsing structures, and tsunamis, resulting about 131 deaths. It lasted four minutes and thirty-eight seconds and it remains the most powerful earthquake recorded in North American history, and the second most powerful earthquake recorded in world history. Tyonek only suffered minor damage due to it being far away from the epicenter. The latest set of earthquakes near Tyonek was an earthquake on Feb 23, 2020, where it was a magnitude was 3.5 earthquake that hit at 7:15 a.m. and was centered in a spot that was 9 miles (15 km) southwest of Tyonek. On March 30, 2020, another earthquake with its epicenter location was 5 miles northeast of Tyonek, with a magnitude of 1.5 strength.

In regards to volcanoes, about 68 miles west of Tyonek is a volcano named Mount Redoubt. It has erupted four times since the 1900’s: 1902, 1966, 1989 and 2009, with two questionable eruptions in 1881 and 1933. The eruption in 1989 spewed volcanic ash to a height of 45,000 ft (14,000 m).

A big fire occurred on May 2014 in Tyonek that affected their 1800 acres of their land. The residents had to be evacuated of the area.

With all these natural hazards of fires, floods, earthquakes, volcanoes, one must really want to live here and put up with these constant life changing events. The Alaskan natives have been here for over 1800 years for many reasons: the beauty of the land, traditions and heritage of the people have their own space, and surviving on the subsistence living. These Alaskan natives have decided to put up natural hazards as part of life: home sweet home.

Second part of this study of the settlement regarding Tyonek is the human geography. Dena’ina Athabascans arrived in the Cook Inlet region between 500 and 1000 AD. In pre-contact times, it is estimated that 4,000-5,000 people were living in West Cook Inlet within the Tyonek Tribal Conservation District boundaries.

Records show that for the past 1000 years, the people of and from Tyonek embrace a culture rich in the long-held traditions, have their own song, dance, storytelling, and religion. “Tebughna,’ which translates as “the Beach People,’ is the name for the people from Tyonek. They lived a subsistence lifestyle (and many still do), relying on the rich natural resources of the Cook Inlet. Hunting, trapping, fishing, and whaling have always sustained the people of Tyonek.

Tyonek first appeared on the 1880 U.S. Census as the unincorporated “Toyonok Station and Village”. It featured 117 residents, including 109 Tinneh, 6 Creole (Mixed Russian & Native) and 2 Whites.

At the 2000 Census there were 134 housing units at an average density of 2.0/square miles. The racial makeup: 4.66% White, 95.34% Native American, and 2.59% of the population were Hispanic or Latino or any race. As of the census of 2000, there were 193 people, 66 households, and 45 families residing. The population density was 2.9 people per square mile (1.1/km ²). The median income for a household was $26,667, and the median income for a family was $29,792. Males had a median income of $26,250 versus $26,250 for females. About 2.1% of families and 13.9% of the population were below the poverty line. Saint Nicholas Orthodox Church which can be traced its origins to 1891, serves the majority of the village’s residents.

The first recorded encounter between the Dena’ina and the Europeans occurred in May of 1778, when the British naval ships, The Resolution and The Discovery, under the command of the famed Captain James Cook, anchored off West Foreland, near the Dena’ina Villages of Qezdeghnen (Kustatan) and Tubughnenq’ (Tyonek).

In 1794, Captain Joseph Whidley, a Vancouver Expedition, visited Tyonek and found that a Russian fur trade company, the Lebedev-Lastochkin Company, maintained a small trapping station on the site of Tyonek with a residence of nineteen Russians.

Between 1836 and 1840, half of the region’s natives died from a smallpox epidemic.

The Alaska Commercial Company had a major outpost in Tyonek by 1875.

Upon the discovery of gold at Resurrection Creek in the 1880s, Tyonek became a major hub for goods and people seeking to make their fortunes in Alaska.

A saltery was established in 1896 at the mouth of the Chuitna River north of Tyonek.

The devastating influenza epidemic of 1918-1919 left few survivors among the Athabascans.

In the 1950s and 1960s, oil and gas companies began exploring the Cook Inlet region, and when gas deposits were found, then several gas companies moved into the area. In 1965, the federal court ruled that the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) had no right to lease Tyonek lands for oil development without permission of the Indians themselves. Later, oil companies paid $12,942,972.04 to the Natives of Tyonek for the lease of Tyonek lands in order to drill for oil and gas beneath the land. With this money, the people of Tyonek built new housing for their people of Tyonek, a school for the youth, and a new Tribal Center. Also, made improvement of roads, and expanded airstrip. Their school named Tebughna (“beach people’) School and it is home to 35 students, ranging from Kindergarten to the 12th grade. They have 2 teachers for one middle/high school teacher, one elementary teacher, and a principal/teacher.

In 1968, the leaders of Tyonek’s supported and helped fund the Alaska Federation of Natives who spearheaded the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) in 1971. In 1973 and under the agreements set forth under ANCSA, Tyonek formed Tyonek Native Corporation and it then became a federally recognized Alaska Native Corporation. While starting out small, the Corporation has since branched out to create and include many successful subsidiaries and businesses.

From the 1970s to the early 2000s, there was sporadic commercial logging occurred on the lands surrounding Tyonek. Extensive road building has occurred to facilitate the logging of trees and access to drilling sites.

Current power requirements can be met by the Beluga Power Plant in Beluga, Alaska, just northeast of Tyonek. Operated by the Anchorage, Alaska-based Chugach Electric Association. Chugach has a total of five combustion turbines in Alaska and is the primary supplier of electricity in the state, with over 2,000 miles of transmission and distribution lines. The Beluga Power Plant is not only the largest Chugach plant; it is also the largest power plant in Alaska, generating 385MW. The plant is accessible only by barge or aircraft, as no roadways connect to any part of Alaska’s major highway system. Beluga is currently fueled by natural gas, although other more economic and environmentally friendly options are being explored, with an implementation goal around the year 2020.

Tyonek Native Corporation is currently seeking to develop its sand and gravel resource for export to global markets. The North Foreland Facility, is the only all-season, deep-water cargo port. This facility was deemed by many Asian and U.S. firms and governments as one of Alaska’s most cost effective commodity port sites. Built in 1947, this steel and pile supported structure is 1,475 feet long, 17 feet wide, and provides a berthing face of 685 feet. A 174 by 50 feet wharf is also located at the end of the pier. This port not only has the relatively stable climate, including moderate precipitation and mild winters, but also from the deep pier depths; therefore it is subject to less ice than many other locations in Alaska.With its mostly ice-free location on the west shores of the Cook Inlet and large mineable sand and gravel resources, immediately adjacent to the Tyonek Pier, a Tyonek operation offers a unique set of logistics to supply high- quality concrete aggregate supplies to the West Coast and Far East markets. Being already halfway to the Far East markets on the Great Circle shipping routes, there could be opportunities to get back-haul shipping rates on vessels returning empty to Asia. With growing population pressures there is steadily increasing demand to build new infrastructure in the Pacific Rim Nations.

The rapid development that occurred in Tyonek during the 1900s, as well as the history of Russians and Euro-Americans from the past three centuries, and the epidemics that caused major lost oof the Native Alaskan who lived in this area, it has most finitely left an impact on the community of Tyonek and the natural resources in the region.

In the early 2000s, leaders in Tyonek began looking for ways to take a greater role in determining their own natural resource future. With about 190 residents still residing in Tyonek and with the Tyonek Native Corporation having over 800 shareholders that can still practice subsistence hunting, fishing, and gathering within the Tyonek area, their hope is to preserve the culture, traditions, and subsistence practices. Subsistence, or the use of fish, wildlife, and plants for home use, is vital for the community of Tyonek to maintain for generations to come in the future. The strong connection between the people of Tyonek and the land and its resources is intertwined with its culture and history and they seek it to maintain forever.